Welcome back viewers

This month's Forgotten Battle is...

The Battle of Lake George

Intro

The battle of Lake George took place on September 8, 1755, in the north province of what is now New York. It was fought between armies from France and Great Britain. Also involved, were hundreds of Native Americans and colonial militiamen. This battle would be one of the first major victories for the British Army during the French and Indian War.

Part I

The Seven Years' War (or the French and Indian War) began on May 28, 1754, when a detachment of British soldiers and Native warriors ambushed a small group of French soldiers near what is now Farmington, Pennsylvania. Led by George Washington, they quickly defeated the Frenchmen and prepared to question their captives. But before Washington could even begin the interrogation, the war-chief of his Native allies (the Half King) approached the captives and proceeded to tomahawk their leader (Joseph Coulon de Jumonville). His warriors then immediately killed and scalped the remaining captives.

Fearing retribution, Washington pulled his soldiers back from the massacre and began constructing a fort. He called it, Fort Necessity. Unfortunately, the Half King and his warriors abandoned Washington as they were not accustomed to fighting within a fortification. Without his Native allies, Washington and his small army were no match for the 600 French soldiers and Indian warriors that attacked Fort Necessity. The British found themselves both outnumbered and outgunned. The final straw came when it began to rain. The rain wet their gunpowder and left them no longer able to fire. With no options left, Washington surrendered.

In exchange for permission to leave the area with his surviving soldiers, Louis Coulon (Jumonville's older brother) had Washington sign a document written in French. After signing, Washington and his soldiers were permitted to leave. What he didn't know was that the document contained a confession to a deliberate assassination of Joseph Jumonville on the orders of King George II. This document made its way all the way back to France and was presented King Louis XV himself. Angered by this "assassination" of a French diplomat, King Louis declared war on the British Empire.

Part II

To win the French and Indian War, the British knew that they needed to drive the French out of the Ohio country. To do this, they needed to capture the French fortification, Fort Duquesne. A force of 1,400 British regulars and Colonial provincials was formed under the command of General Edward Braddock. Braddock's army marched into the wilderness and began a four week long trek to Fort Duquesne. Unfortunately, on June 9, they were ambushed by a large French and Indian army while crossing the Monongahela River. When it was over, Braddock and half of his army were either dead or wounded.

Two months after this debacle, a new British general from Ireland arrived to lead another expedition. His name was, Sir William Johnson. Unlike Braddock, Johnson knew that the key to victory against the French lied with securing the support of the Native people living in the Ohio country. He had already struck up an alliance and a close friendship with a Mohawk chief called, Chief Hendrick. With Chief Hendrick's help, Johnson hoped to recruit hundreds of Indian warriors from the Iroquois Six Nations to join his expedition.

A few days before General Johnson began his trek into the wilderness, more than 1,100 warriors and representatives from the Iroquois Six Nations arrived to meet with him and Chief Hendrick. For a full night, Johnson exchanged goods with them and took part in their ceremonies. While they appreciated the gifts and his respect for their culture, most of the warriors refused to break their neutrality. In the end, less than 300 Mohawk warriors (mostly belonging to Hendrick) volunteered to accompany Johnson.

Part III

On September 7, General Johnson and Chief Hendrick set off for Fort Duquesne with just over 1,900 British regulars, colonial provincials (militiamen), and Mohawk warriors. After a full day of marching without incident, they finally arrived at the south end of Lake George and set up camp. Early the next morning, Johnson and Chief Hendrik resumed their march on Fort Duquesne. They had no idea that they were walking into a trap.

Late on the night of September 7, a force of 1,500 French soldiers, Canadian militia, and Indian warriors arrived at the north end of Lake George. Under the command of Major General Baron Dieskau, they moved to a ravine that blocked the portage road that Johnson's army was using. With the warriors and militiamen positioned on both sides of the road, the French grenadiers aligned themselves directly in-front of the oncoming British and Indian force. The fighting began at 9:00 the morning of September 8. This part of the battle would later be referred to as the, "Bloody Morning Scout".

Chief Hendrick and many of his warriors and colonial militiamen were ambushed by Canadian Mohawk and Abenaki warriors while scouting ahead of the main British force. Before long, Hendrick and most of his men were dead. Those who survived quickly retreated four miles back to Johnson's camp. After being informed of the ambush, Johnson quickly organized an improvised defensive barricade around his camp. Using wagons, overturned boats, and felled tree branches, they prepared to meet the oncoming attack.

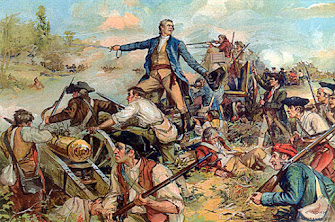

Against the advice of his Indian allies, Baron Dieskau had decided to follow up on his successful ambush by attacking the British camp. An hour and a half after the Bloody Morning Scout ambush, Dieskau arrived at Johnson's position and ordered a direct attack. As the French grenadiers approached the camp in column formation, Johnson had his soldiers hold fire until the last possible moment, then they unleashed a deadly volley. Johnson's three cannons were loaded with grapeshot and proceeded to decimate the French and Canadian ranks. When Baron Dieskau fell severely wounded, the French and Canadians retreated in disorder.

Epilogue

Later in the day, the British and colonials successfully ambushed and annihilated a French baggage train resting by small pond (later called, Bloody Pond). After this, the outcome of the battle had been cemented. The casualties were heavy for both armies. The British are believed to have suffered over 300 total casualties (among the wounded was General Johnson). The French and Indian casualties are believed to be around 350 killed, wounded, or captured. Among those to be captured was Baron Dieskau. He would remain a POW for the next eight years.

After their defeat, the French retreated back across the lake, appointed a new commander (the Marquis Louis-Joseph de Montcalm) constructed a new fortification called, Fort Carillon. Although he had not reached his target (Fort Duquesne) Johnson's expedition had been able to gain a successful foothold in the Ohio country. He consolidated his victory by building a British fort at the south end of Lake George which he called, Fort William Henry. Although fierce fighting would continue until 1763, the British victory at Lake George was considered their first major success in the French and Indian War. One that help to secure a hard-fought victory in the future.

http://nyindependencetrail.org/stories-Battle-of-Lake-George.html

https://www.lakegeorge.com/history/battle-of-lakegeorge/

https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/battle-of-lake-george-1755/

https://www.nps.gov/people/tanaghrisson-the-half-king.htm

https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/fort-necessity/